Thirty-four years ago, at the launch of Ted Turner's Cable News Network, the founder made a grandiose and specific promise about his newly created round-the-clock operation. "Barring satellite problems, we won't be signing off until the world ends," Turner declared. And in anticipation, he prepared a final video segment for the apocalypse:

We'll be on, and we will cover the end of the world, live, and that will be our last event. We'll play the National Anthem only one time, on the first of June [the day CNN launched], and when the end of the world comes, we'll play 'Nearer My God To Thee' before we sign off.

People thought he was joking. We have proof, acquired from a source, that he wasn't. Below is the never-before-seen video the last living CNN employee will be required to play before succumbing to radiation poisoning, the plague, zombies, or whatever crazy end Turner saw coming.

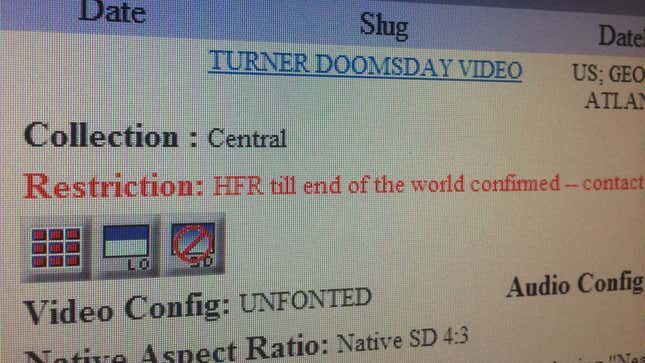

It lives on CNN's MIRA archive system, under the name TURNER DOOMSDAY VIDEO. Reflecting its status as an artifact, not to be used except in the ultimate emergency, it's in standard definition, with an aspect ratio of 4:3, perfect for the cathode-ray tube televisions of the 1980s.

The video has already outlasted Ted Turner's ownership and the rise and fall of AOL. If it has not yet had the chance to serve as the capstone of all human experience, it nevertheless stands as a quiet monument to the globe-girdling ambitions behind CNN.

CNN may be the human centipede of journalism at this point, its bloated corpse stumbling through the supposed middle ground of the wasteland that is American cable news, but it wasn't always that way. It was founded almost as an ideal, and much of the media world owes its very nature to the first cable news network.

Before CNN, a regular person could absorb the news only in restricted doses, at specific times of day. Turner's innovation was in the idea of news without boundaries, night into day into night again, allowing anyone to be an obsessive media nut, every single second of every single minute of every day.

From 1980 on, news would always be there for you, right until the very end. At its birth, the now-moribund news giant operated like many of the new media organizations of today—hiring young people with little experience and plenty of drive, people who wanted the breathing space to explore every story that couldn't fit into a 30-minute news segment.

Since those early years, CNN has grown into a ponderous object in the background, immovably entrenched on cable even as it has been tossed from corporate merger to corporate merger. Born as part of Ted Turner's Turner Broadcasting System, in 1996 it became a part of Time Warner. In 2000 America Online bought Time Warner for $164 billion, and in 2006 Ted Turner himself left the Time Warner board. In 2009, the biggest corporate mistake in history reached its inevitable conclusion, and AOL was spun off from the company it once attempted to dominate.

Through it all there have been monumental culture shifts and budget re-adjustments, ideas tried out and tossed aside. There are few vestiges left of its original promise.

But there is still the video, awaiting its deployment. I was an intern at CNN back in 2009. Specifically, I worked at the Situation Room with Wolf Blitzer. Wolf was a nice enough guy, as people from Buffalo tend to be, but that's not really so weird. What was weird was seeing the apocalypse video.

I was originally told about it by a college professor of mine, who had worked at CNN for over 20 years. It sounded mostly like a mythic joke, the kind of thing that Ted Turner, the all-around "eccentric billionaire" archetype, would mention offhand. Bison ranches, the America's Cup, four girlfriends at once, the last word on the last day on earth—why not?

Turner's boast about broadcasting through the end of the world is the kind of thing you hear, in one form or another, from every startup founder. My idea is the best, it will beat all the others, it is here to stay, forever and ever. No, we won't get bought by AOL. And Turner was known for being blustery.

So when Ted Turner said that CNN was going to be playing "Nearer My God To Thee"—the song the band supposedly played when the Titanic went down—as the heavens opened up, as the fiery finger of God rained salt and brimstone from the sky, as the Earth beneath our feet opened from below and swallowed everything above, as the last CNN employee, in the last surviving CNN studio in the world, witnessed the end of existence before them, he meant it.

Rumors of the doomsday tape's existence have popped up from time to time, as early as 1988, in the case of the New Yorker, and as late as 2001, in the Daily News.

Few internal projects in media companies have that sort of staying power, but despite all the whiz-bang tech CNN likes to display on air, everything behind the scenes isn't so new.

In contrast to CNN's ideas of what to put on television, all flashy smiles, enormous screens, and the occasional hologram, behind the scenes things can still be a little archaic. I don't remember the exact day that I saw it, but it must've been a slow day in between all the regular intern duties of cueing up tapes and distributing mail. Maybe I should've been busier, but this was back in the Situation Room's days of covering the Balloon Boy saga, and so there weren't many obstacles in front of a bored college student looking to indulge his overcharged sense of curiosity.

The video didn't take long to find; it turned up after a quick search in the database. There is no date attached, but the title reads "TURNER DOOMSDAY VIDEO."

Should you find yourself watching the apocalypse live on CNN, the last thing you see will emphatically not be in 4K resolution.

It's kept behind its own proverbial glass case. Angry, bold red letters are rendered on the computer screen of anyone who comes near it on CNN's intranet video database, reminding whoever accesses it that there is a grave restriction:

HFR till end of the world confirmed.

Hold for release. CNN, once ever so thorough in its factchecking, knew that the last employee alive couldn't be trusted to make a call as consequential as one from the Book of Revelation. The end of the world must be confirmed.

That leaves open a whole host of unanswered questions. If this is the last CNN employee alive, in the last CNN bureau on Earth, who do they confirm it with? What does confirmation look like? Who can be the one to make that determination, to pronounce the universe itself dead? Is it Wolf Blitzer himself, ever a fan of the Washington Wizards, and thus a man who would know death when he saw it? Would it be Rick Davis, CNN's head of standards of practices, who has been with the company since its birth and who thus would know CNN's journalistic practices better than anyone?

Or would it be some sort of living embodiment of CNN itself, ready to proclaim its own demise, as Judgment Day is truly the only thing able to bring about the long-anticipated death of cable news?

And who would be around to watch it?

We don't know.

All we have is this bleak yet romantic farewell, showcasing both the best and the worst of humanity with all of its unsettled questions. Like nuclear weapons or the little safety card they give you on the plane, it's the fact that we don't know why or how exactly we'd need it that stands as the most unsettling thing about the doomsday video. This may just be the last thing that whoever is left sees, watching on whatever device remains, when humanity's last remnant winks out of existence.

So, in one small regard, this is actually the way the world ends. This is the way the world ends, not with a bang, not with a whimper, but with one melancholy little band, and a quick fade to black.

Note: Since this article has gone up, we've been getting a number of questions as to how we obtained the footage. While we can't go into specifics, it's not something we've been sitting on since I was an intern in 2009. While I've been aware of its existence since then, it was only acquired after I came onboard here at Jalopnik.

Illustration/video thumbnail by Jim Cooke, Video assistance from Nick Stango and Chris Person